aeon

San Francisco’s homeless are harangued and despised while conservative Utah has a radically humane approach

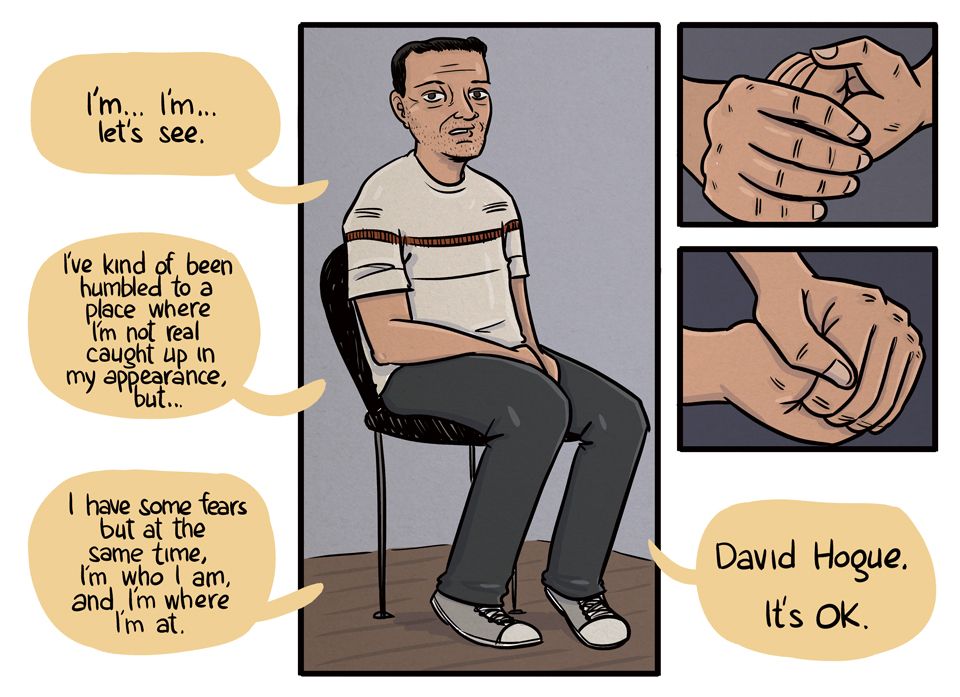

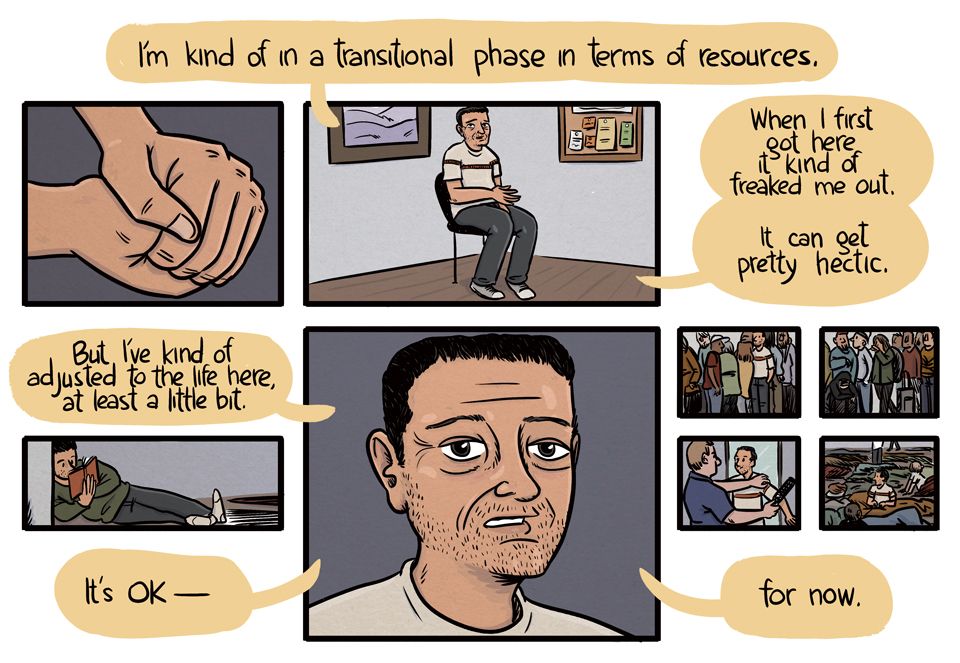

David Hogue isn’t sure that he should tell me his name. He sits in a back office in the shelter where he has lived for the past 18 months, hands folded neatly in his lap. It isn’t that he doesn’t want to talk. He tells me about how he’s had trouble finding work. He tells me about how he’s bounced between homes for years. He tells me about how his brother dropped him off here the day after New Year’s.

But to identify himself as homeless – this is new.

The condition of homelessness is fluid, and so is our definition of it. The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) placed the homeless population in January 2014 at 578,424, but advocacy groups such as the National Student Campaign Against Hunger and Homelessness say that more than 3 million Americans experience an episode of homelessness each year: a night, a week or a month in a motel, in a recreation vehicle or on a friend’s couch might not make you ‘homeless’ in the eyes of the federal government, but they certainly define your lived experience.

The US has always had many shades of destitute, but this particular era of homelessness marks a new chapter in the country’s history. The causes of this crisis are no great mystery. Real median household income has plateaued since the 1960s. Adjusted for inflation, minimum wage has fallen since the 1970s. After the manufacturing industry contracted and unemployment grew in the 1980s, the homeless populations in US cities rose precipitously. For the first time since Hooverville – the shanty town built by homeless people during the Great Depression of the 1930s – American poverty was laid bare in its parks and on its streets. Since then, about 600,000 people have lived without a home on any given night in the US.

In every housing market, minimum wage is not enough to afford the average two-bedroom rental. Federal and state programmes to support and serve the mentally ill have been all but entirely dismantled. And the highest prison incarceration rate in the world has only further destabilised poor communities. For the most part, homelessness has been approached as a natural and inevitable plight of contemporary urbanity: a thing to be managed, not fixed.

But now a new optimistic ideology has taken hold in a few US cities – a philosophy that seeks not just to directly address homelessness, but to solve it. During the past quarter-century, the so-called Housing First doctrine has trickled up from social workers to academics and finally to government. And it is working. On the whole, homelessness is finally trending down.

Get Aeon straight to your inbox

The Housing First philosophy was first piloted in Los Angeles in 1988 by the social worker Tanya Tull, and later tested and codified by the psychiatrist Sam Tsemberis of New York University. It is predicated on a radical and deeply un-American notion that housing is a right. Instead of first demanding that they get jobs and enroll in treatment programmes, or that they live in a shelter before they can apply for their own apartments, government and aid groups simply give the homeless homes.

Homelessness has always been more a crisis of empathy and imagination than one of sheer economics. Governments spend millions each year on shelters, health care and other forms of triage for the homeless, but simply giving people homes turns out to be far cheaper, according to research from the University of Washington in 2009. Preventing a fire always requires less water than extinguishing it once it’s burning.

Related video

VIDEO

Is the introspection of self-help and therapy hurting our ability to empathise?

10 minutes

By all accounts, Housing First is an unusually good policy. It is economical and achievable. The only real innovation lies in how to inspire the necessary compassion and foresight to spur governments into building those needed homes.

But Housing First is not very popular. It runs directly counter to the US meritocratic mythology, where one is presumed to fail or succeed by one’s own hand. The homeless are presumed to have earned their place on the street.

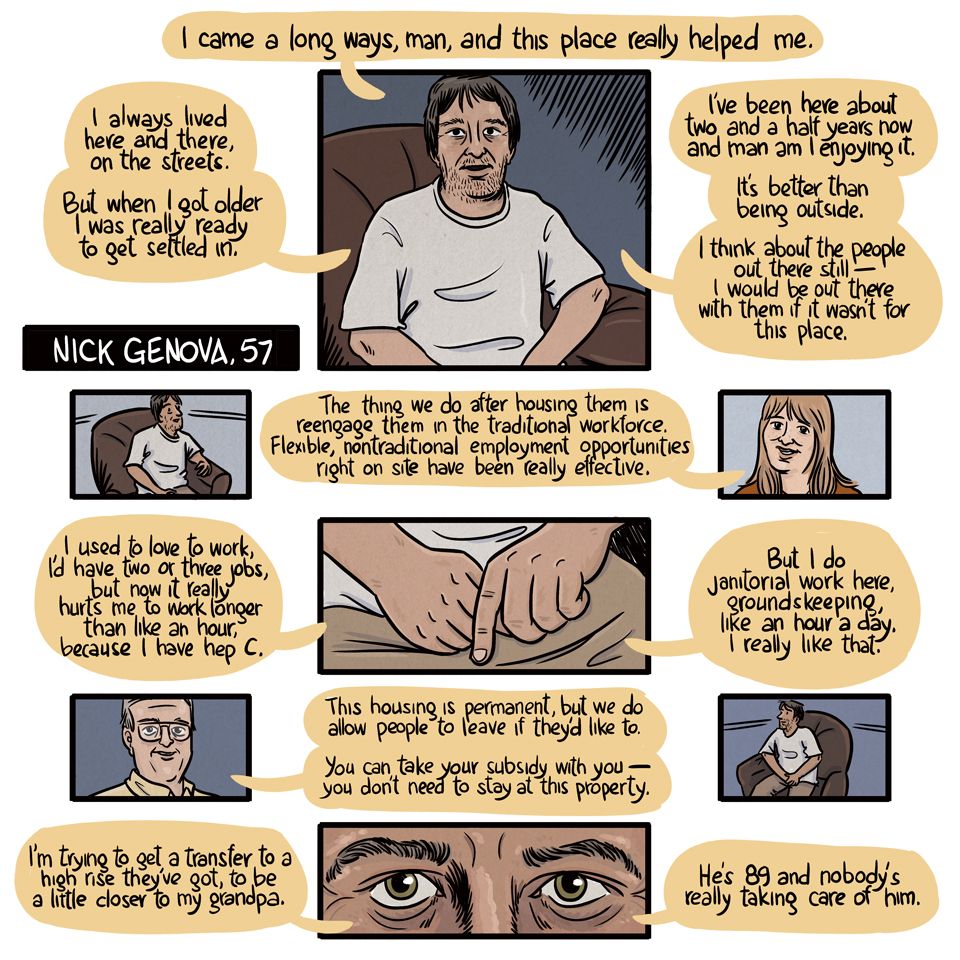

Precious few places have had the nerve to fully implement a Housing First policy, though hundreds of cities have drawn up the plans. But the approach has been successful in Utah, where chronic homelessness is down 91 per cent over the past decade, and where rapid rehousing programmes have housed thousands of newly homeless veterans and families quickly and cheaply. To the surprise of every self-described progressive, Utah has emerged as a model for municipal programs around the country.

The spread of Housing First could usher in a new kind of compassionate governance in a new era of urban growth – but like any policy, its application is limited. The programs are available only to a small subset of the homeless: those with disabling conditions such as mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction, whose lives and habits place the biggest financial burden on the state. They are not available to people such as David Hogue, at least not until he becomes more desperate and his plight is deemed too expensive. Even at its most robust, our social safety net is hung very low to the hard ground.

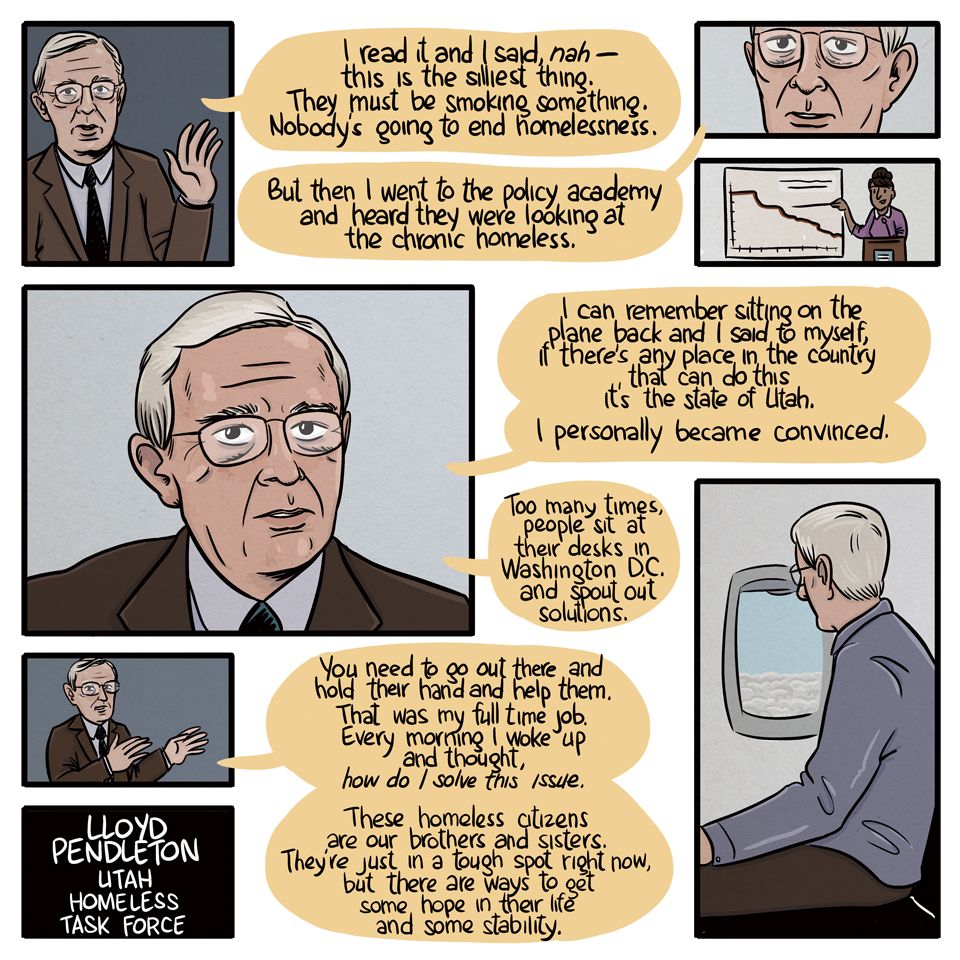

When the federal government embarked on its first significant plan to ‘end homelessness’ more than a decade ago, it seemed less a clear, developed strategy than a kind of dream.

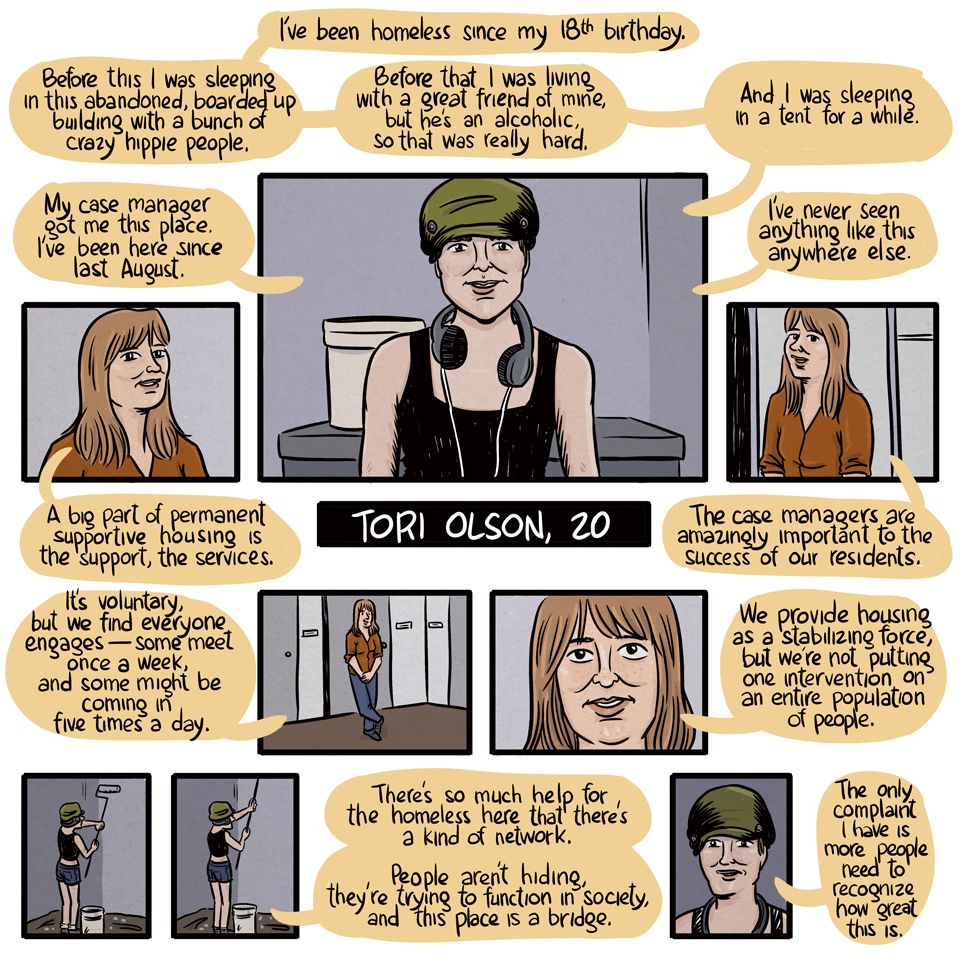

If progressives are surprised by Utah, they will be horrified that Housing First began under President George W Bush. Between 2002 and 2003, hundreds of service providers and local officials met in Washington, DC to learn about the policy. Housing First generally comprises two prongs: permanent supportive housing for the chronically homeless, defined as those prone to long bouts of homelessness as well as substance abuse or mental health issues; and rapid re‑housing assistance for the less acutely homeless, who are typically aided in finding a home rental and given basic living funds for a few months to help stabilise them.

Representatives from cities and states across the US spent the policy camp devising ambitious plans to reshape their communities, but Utah was one of the precious few to actually implement theirs.

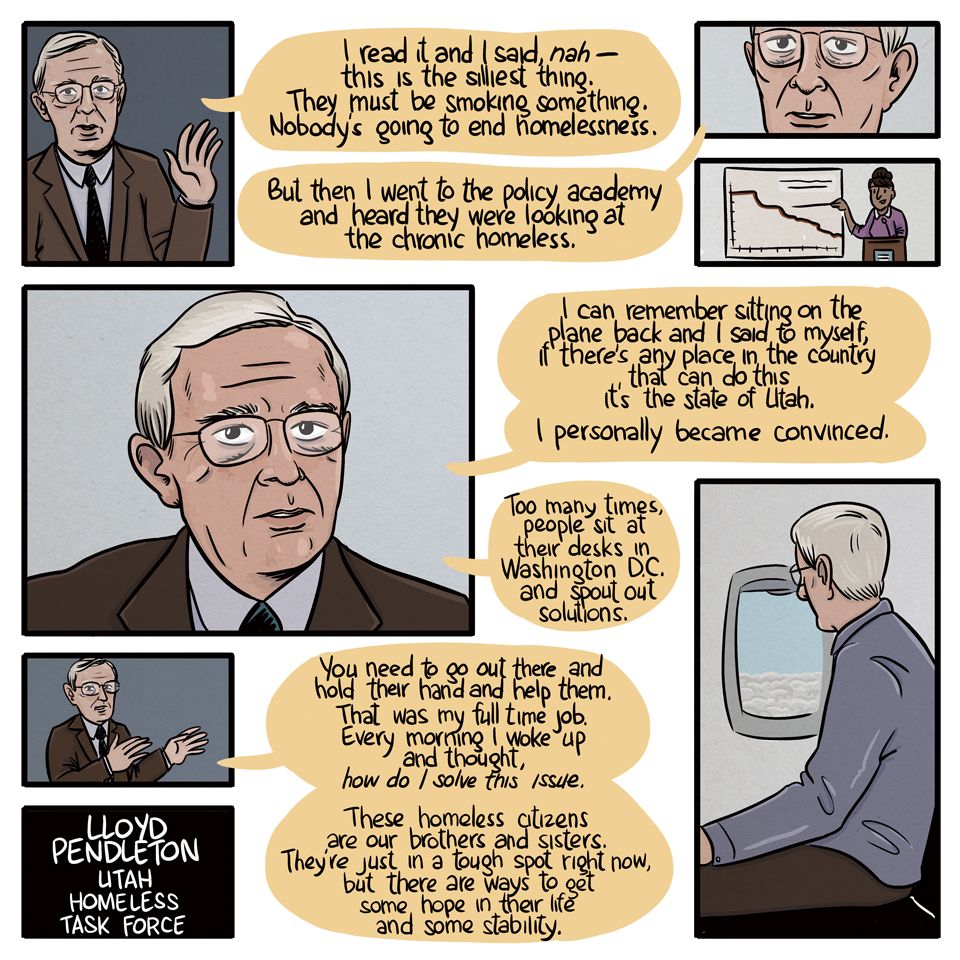

‘People ask, why Utah?’ Lloyd Pendleton, the head of Utah’s Homeless Task Force tells me. Pendleton spent years as an executive at Ford Motors before taking a job managing resources at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS) that put him in close contact with service providers and aid groups across the state. After that 2003 meeting, he asked the Church to ‘loan him’ to the government to devise the plan, and later took the position at Utah’s Homeless Task Force. At the time, Utah had a fast-growing homeless population, a strong and homogenous local community, a faith-based ethic of mutual aid, resources, and, in Pendleton, a uniquely empowered champion.

In 2010, President Barack Obama’s administration released its ambitious plan for a reboot of the programme first started under Bush. The Obama plan was released quietly, but it came with a mandate and a timeline: to end chronic and veteran homelessness by 2015, and family and child homelessness by 2020. By then, Utah’s Housing First pilot programme had already proved successful: 17 of Salt Lake City’s most troubled and most expensive homeless people were given their own apartments.

Nowhere else is quite like Salt Lake City, ‘the Crossroads of the West’, first settled by a desperate people with nowhere else to go. The Mormons who established the state in religious exile were close-knit, self-sufficient, and passionate about their personal liberty. This was never a community with much regard for the laws and policies of a hostile federal government, and that spirit has never really changed. On some points, this slice of the Wild West appears conservative: there’s an emphasis on preserving personal freedoms, and no particular love for taxes. But on others, this culture born of a very independent yet interdependent commonwealth is more truly progressive than any ‘blue-collar’ state.

When I visited Utah, people kept telling me that collaboration made this shift possible. For the most part, the only people who care much about the homeless are the people whose job it is to do so. Pendleton made it his mission to change that. With his background in corporations and the Church, he was successful in bringing government, non-profits, faith-based organisations, and business leaders to his table. He was able to persuade them that homelessness required a solution that went far beyond the capacity of traditional social welfare services. This seems obvious but proved radical: no longer could service providers compete with one another for the same funding, and neither could business leaders complain about the visible homeless but claim that they had no say in the solution.

‘When you go to a homeless summit, the only people there are homeless service providers,’ Pendleton tells me. ‘You need that higher community buy-in, a higher level of coordinated effort.’

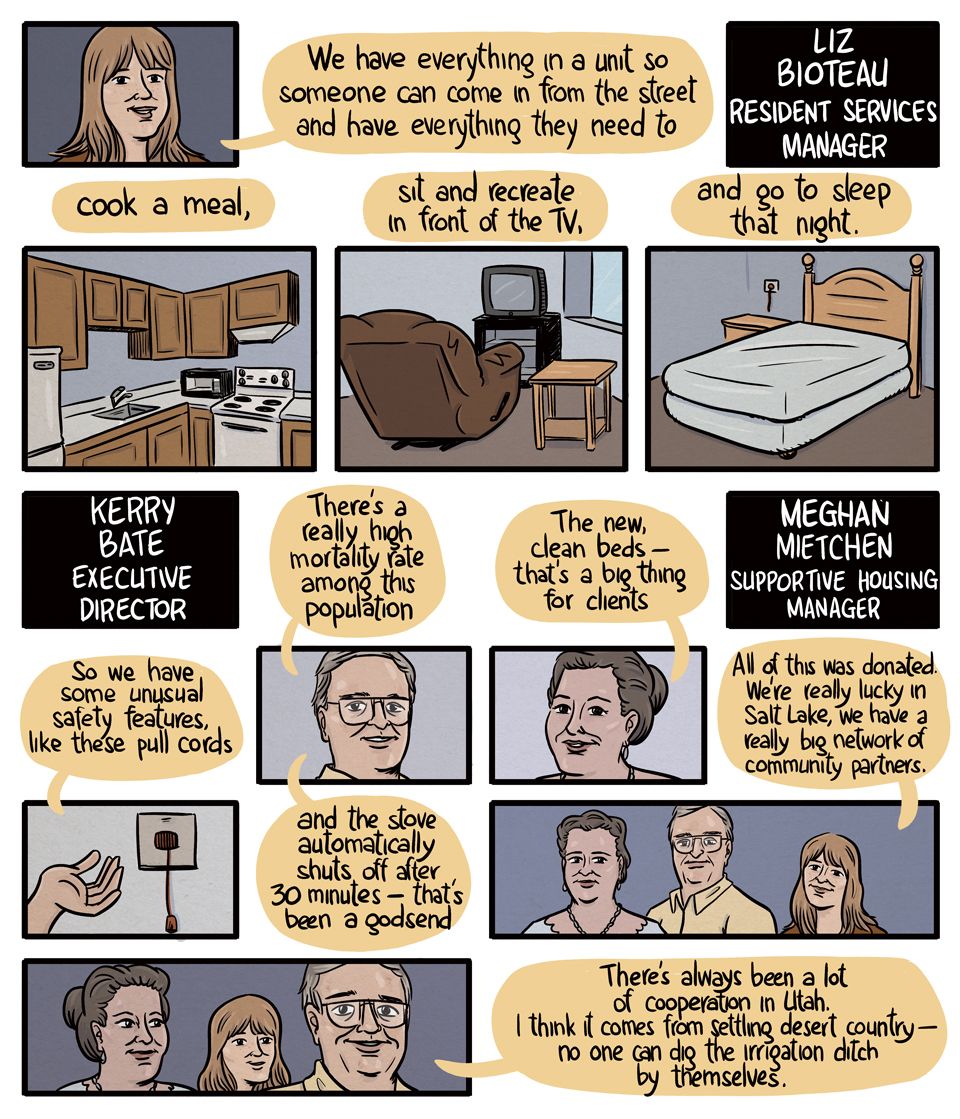

This daisy chain of partnerships includes the non‑profit organisation Housing Opportunities, which develops and manages dedicated permanent supportive housing facilities across the greater Salt Lake County area.

Housing Opportunities’ apartment buildings are located away from the downtown business district and closer to residential areas. They feel more like college dorms than institutions. Communal areas, gyms, computer labs, libraries, community gardens and athletic facilities – it’s safe to brag about the amenities when all of this is cheaper than the alternative.

This kind of permanent supportive housing is developed by both public and private non‑profit entities using established funding streams already dedicated to affordable housing programmes. In Salt Lake County, the Road Home non-profit and the Housing Authority of Salt Lake City also operate similar dedicated facilities for families and individuals. Permanent supportive housing programmes also place the homeless in regular Section 8 housing, under which landlords accept housing vouchers in lieu of payment.

The rent is, at minimum, $25 per month, or one-third of a resident’s income if there is any, which some earn by working janitorial, clerical or landscaping jobs at the facility. The rest of the cost is subsidised by pre-existing HUD funding and special grants.

While it looks like its own separate policy structure, Housing First is truly just a reconsideration of entrenched housing programmes and budgets. Utah is not especially rich compared with other states, and its chronic homeless weren’t so uniquely inexpensive as to leave the state with the surplus it needed to build this new infrastructure. Much of the work of housing support staff is spent searching for a particular grant, voucher or other funding stream that best fits each client.

On my way to Utah this May, I read a letter to the editor in a local Salt Lake newspaper, decrying Housing First as wasteful, hopeless and a general insanity. Advocates in Utah tell me this isn’t a terribly common refrain. But it speaks to entrenched US attitudes that could forestall the wide‑scale adoption of the Housing First approach.

Americans have a deep and abiding faith in the strength of one’s own bootstraps – regardless of whether or not one can afford boots. The prevailing system of subsidised housing in early US history was the workhouse or poor farm, where the otherwise homeless endured hard manual labour in exchange for meagre accommodations. It wasn’t until President Franklin Roosevelt’s sweeping New Deal that the nation’s first public assistance programmes were established in the 1930s, including subsidised housing. But in the decades since, those programmes have, in many ways, come to look more like the old workhouse than progressive social policy.

Aid is almost always predicated on a system of incentives: a Rube Goldberg machine of carrots, sticks and innumerable pulleys to wrench the homeless constantly in new and opposing directions. Assistance is given conditionally and you must earn it, just as you are presumed to have earned your place in hardship. Temporary transitional housing programmes, which are still the dominant form of housing available to the homeless in the US, hinge on righteously rewarding good behaviour – participation in drug treatment programmes, successful performance at a job – and punishing bad behaviour with eviction.

Since the recession of the previous decade, more than 20 US states proposed laws to require all applicants for public assistance to pass a drug test. Those laws were ruled unconstitutional, but at least 13 states have passed legislation requiring some recipients of food stamps, welfare or other public assistance to submit to drug testing, and at least 18 more states have proposed similar laws.

In this cultural environment, it’s best to pitch Housing First not as a holistic ideology that reimagines the true nature of the social safety net and the rights of individuals, but as a strict cost‑saving measure: the carrots are far less expensive than the sticks, at least for those at the extreme ends of homeless life.

If Utah is the ideal model, then Hawaii has become the cautionary tale. Article 9, section 10 of the Hawaii state constitution is a precept in native Hawaiian law, the Law of the Splintered Paddle. It was first established by King Kamehameha in 1797 with the intent of protecting the poor:

Oh people,

Honor thy god;

respect alike [the rights of] people both great and humble;

May everyone, from the old men and women to the children

Be free to go forth and lie in the road (ie by the roadside or pathway)

Without fear of harm.

Break this law, and die.

In the ensuing centuries, the Law of the Splintered Paddle has been reconsidered as a statement on public safety as homelessness has been criminalised. It is easy to live without a home in temperate and traditionally culturally tolerant Hawaii. This has long frustrated the state’s more conservative politicians, who first offered the homeless strange carrots – plane tickets back to their home communities – before resorting, quite literally, to sticks. In late 2013, the state representative Tom Brower took a ‘tough-guy’ approach to the state capital’s homeless problem, by smashing any shopping cart he found with a sledgehammer, after thoughtfully removing the homeless person’s belongings from it first. Recently, Hawaii killed a proposal for a homeless bill of rights, and upheld a law banning people from sitting or lying on public sidewalks.

Bans on sitting or lying in public spaces have also been instituted in California, in such progressive bastions of hippie idealism as San Francisco, Santa Cruz and Berkeley, and nearly one-third of other US cities. Bans on begging, sharing food with homeless people and sleeping in cars make the homeless life nearly impossible in hundreds of other US cities. These policies are predicated on the reality that homelessness is a local problem, and the fantasy that, if driven to the most rural parts of the country, the homeless will simply cease to exist. These laws are good for property values, but not for city budgets – a study by the University of California, Berkeley in 2015 found that they prove expensive to enforce.

Cities these days have less and less room for the homeless, the poor, and even much of the middle class. New demand for urban life has far outstripped the housing capacity of most major cities, and every county in the US is facing an affordable-housing crisis. Where cities were once the easiest place to be poor, with access to services, aid, transit and small housing accommodations, they’ve now become nearly impossible.

Alongside this new economic pressure, a wave of self-described progressive policies has reclaimed urban spaces in the name of sustainability and innovation. Urbanists say that cities are our innovation hubs, our policy labs. Many of the cities with the most passionately stated progressive politics are the ones with the most expensive housing markets and the most desperate homeless communities. These are the places we’ve come to associate with innovation.

The most substantive critiques of Housing First point to this larger economic reality: homelessness is a problematic condition, but it is not the problem in itself. Our economic policies guarantee that there will always be someone left behind, and without addressing this core problem, any triage can’t really stem the bleeding. In the meantime, every policy is, by its nature, a half measure. Unfortunately, there is a growing market for quick fixes masquerading as solutions for systemic problems. ‘Teach the homeless to code’ was a joke before it was a reality in San Francisco, followed soon by the homeless shower bus, and innumerable homelessness-solving apps.

When the tech worker Greg Gopman wrote a Facebook post decrying San Francisco’s homeless and comparing them to wild animals, he was righteously vilified. Gopman atoned for his sins by performing light community service with local homeless groups, and then reimagined himself as a homeless advocate and new solutionist. Gopman’s latest plan to solve homelessness involves building intentional communities made up of tiny geodesic domes furnished only with a bed, for which residents pay $250 per month for a maximum of six months. Residents must be sober and have no history of mental illness.

Gopman calls these ‘transition centres’, a nod to the transitional housing model that cities are rejecting in favour of permanent housing. He’s currently seeking ‘investors’. When I tell service providers in Utah about Gopman, they look at me like they smell something rotten.

Those who cheer Utah’s impressive success have repeatedly called the Housing First programme ‘shockingly simple’. This would be lazy if it weren’t also wrong. In reality, Housing First is incredibly complex, and requires a very specific set of conditions in order to actually work. If cities set out to solve this complicated and expensive social problem before they’ve embraced the underlying philosophy that housing is a human right, they are likely to fail.

Despite its remarkable run in Utah, Housing First has been slow to spread through the rest of the US. Since 2002, cities and states have implemented Housing First ideas with varying degrees of success. Houston and New Orleans achieved their initial goals, but Seattle failed – because, according to the director for the city’s largest non‑profit service provider, it didn’t implement Housing First at the scale the city required.

Pendleton’s successes at Utah’s Homeless Task Force attracted media attention, including an appearance this January on The Daily Show, which made it possible for Pendleton to begin consulting cities on how to do what he did.

‘I’m looking to find an Orlando, a Denver, that’s serious about making this happen,’ Pendleton tells me. ‘My goal personally is to find a half a dozen states or counties or cities, and become a regular participant with them and say here’s how we did it, here are the principles, now let’s find the champions locally.’

But heroes and ideas alone do not make change. What made Utah’s programmes successful was concentrated power and wealth in the LDS Church – the Church that Pendleton brought to the table. Kerry Bate, the executive director at Housing Opportunities, recounts how they organised congregations to assemble the furniture for all of the apartments – which they’d also donated. It took only a few hours. ‘The Church can go both ways,’ he tells me. ‘It can smother you or you can blossom.’

There are, however, still homeless people in Utah. This seems an important point to mention, if a painfully obvious one. The Road Home shelter has never had to turn anyone away, says its housing director Melanie Zamora, but its 850 beds are full each night, and hundreds more homeless sleep in the city parks, under bridges and along the river.

Like many major US cities, Salt Lake is gentrifying, too. It is one of the only places where median wages have outpaced median housing prices, but the city is still short of thousands of necessary affordable-housing units, and homelessness overall has increased precipitously since the recession. Downtown near the Road Home, dozens of the homeless spend their nights inside a shelter, and their days in the nearby streets and parks. Blocks away, renovated condo lofts are selling at a premium, and cranes work morning to night to build more. One developer began a neighbourhood group and campaign to move the shelter to the other side of the freeway, where the real estate is less valuable and accessible. It would be a lucrative move for Salt Lake’s housing market, and a significant blow to housing the homeless.

It is not that Housing First is broken, it’s just that it’s not nearly enough.

For people such as David Hogue, this all amounts to cold comfort, the policy equivalent of the hard mats you have to sleep on if you arrive too late at the shelter to get a real bed.

For Hogue to receive more help, his intolerable condition must become even more intolerable.

‘He’s been here for a year and a half – but he’s not chronically homeless?’ I ask Zamora.

‘If we don’t do something soon, he will be,’ she says.